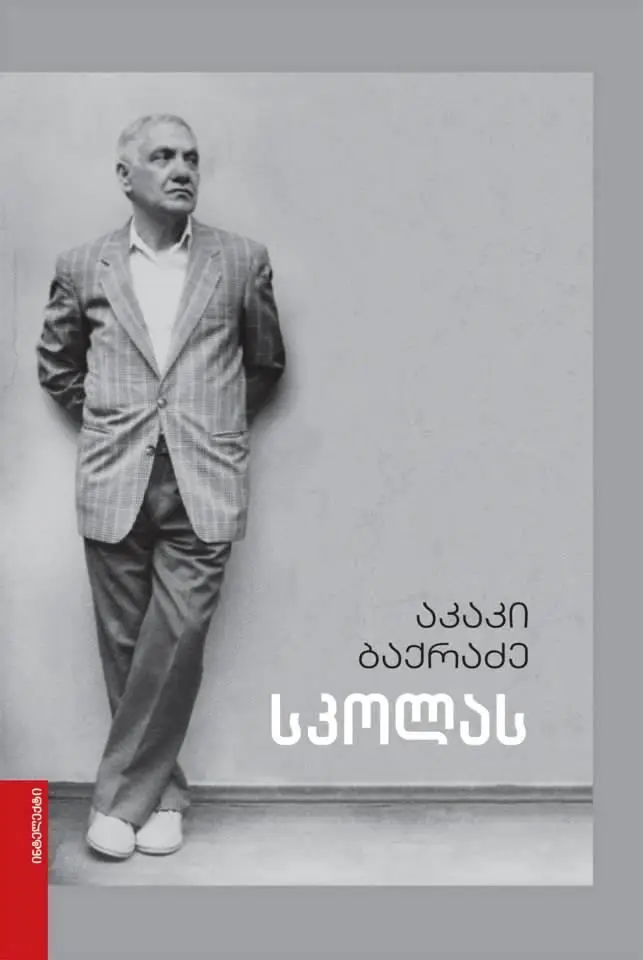

In the late 1970s, I was lecturing at the university. By 1983, I decided to turn those lectures into a book, which I titled The Taming of Literature. It was a substantial manuscript—of course, at the time, publishing it wasn’t even a possibility. But still, it was read by Nino Adamia, Mikheil Antadze, Amiran Gomarteli, Leila Nanitashvili, Aleksandre and Nanuli Papava, Nodar Tsuleiskiri, and others.

When I wrote The Taming of Literature, my aim was not to accuse or scold anyone. I never assumed I would have acted differently had I been in their place. No one knows how they would endure torture—when a needle is driven into your ear, or you’re mutilated, hung upside down, beaten with iron rods, or forced onto a bottle. Only if you have faced such things and not broken do you earn the right to look at others with judgment or forgiveness. But when you lie in comfort, far from danger, it’s easy to play at morality and condemn others.

What I wanted was simply to portray a picture of the time, with documents, and to show the fate of the human being trapped within it, especially the writer. Today, publishing The Taming of Literature is possible. Some may find it dated, but much of what I feared came to pass.

European culture nurtured the ideal of personal and national freedom among the conquered peoples of Africa and Asia—it awakened them. Russian culture, on the other hand, offered no such ideal. It produced instead new forms of enslavement, of both the individual and the nation, and found a new path to Russification, under the banner of socialism.

— Akaki Bakradze, The Taming of Literature